Cover glasses were prepared on a 24-well plate and were treated with Poly-L-lysine solution (Sigma) for seeding cells. The cells were stimulated with ligand cGAS-STING (ISD (1μg/ml)-lipofectamine 2000), or several TLR ligand, for various time points. Then, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Nacalai Tesque) for 20 minutes at room temperature. After washing three times with 0.02% Triton X-100 in PBS, 100 mM glycine in 0.02% Triton X-100/PBS was added at room temperature for 30 minutes. Cells were washed 3 times with 0.02% Triton X-100 in PBS and were blocked with 10% FBS, 0.02% Triton X-100/PBS for 1h at room temperature. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted with 10% FBS 0.02% Triton X-100 at 4 °C overnight. After washing three times with 0.02% Triton X-100, cells were applied with the secondary antibodies diluted with 10% FBS in 0.02% Triton X-100 and were incubated for 1 hour. After three times washing with 0.02% Triton X-100, Hoechst 33342 (Dojin) was diluted with 10% FBS in 0.02% Triton X-100 and incubated for 10 minutes. After 3 times washing with 0.02% in Triton X-100, samples were enclosed on slide glasses with Fluoro-KEEPER Antifade Reagent, Non-Hardening Type (Nacalai Tesque). The prepared samples were observed with confocal fluorescence microscope LSM 700 (ZEISS), and images were processed with ZEN software. Dilution ratios of the primary and secondary antibodies are shown below.

paper publication that I wrote as reference, feel free to discuss and citation.

http://www.jbc.org/content/early/2019/04/03/jbc.RA118.005731.long

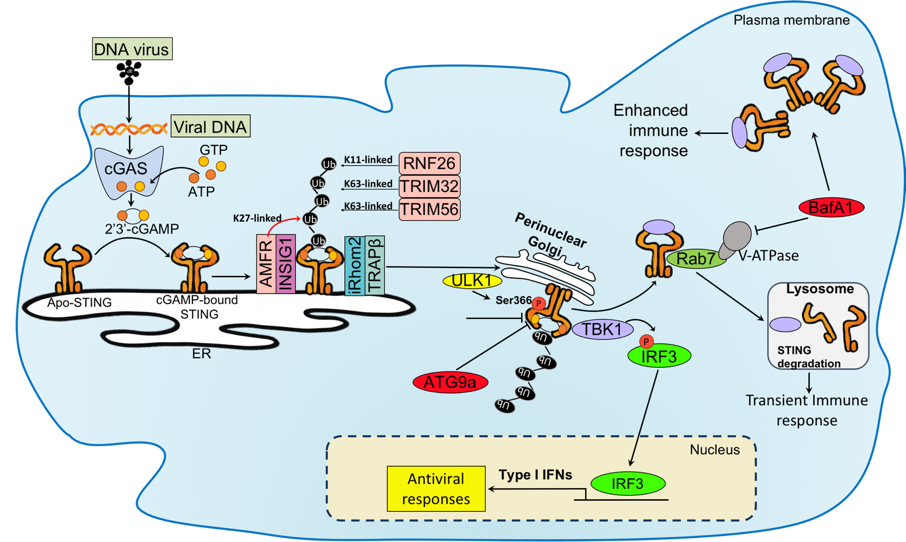

Various regulatory mechanisms for cGAS and STING pathway have been shown (Cai et al., 2014; Chen and Chen, 2016; Liu et at., 2015; Liu and Wang 2016; Hu et al., 2016). Sumoylation and Mono-ubiquitination of cGAS at Lys355 that are induced by E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM56 is important for its DNA sensing activity, resulting in increased cGAMP production (Xiong et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2013; Seo et al., 2018). STING moves from ER to Golgi apparatus via the translocon-associated protein (TRAP) complex TRAPb(SSR2) that is recruited by inactive rhomboid protein 2 (iRhom2) and these complex reaches to Sec-5 containing perinuclear microsome or cytoplasmic punctate structures to assemble with TBK1 and IKK complex (Ishikawa et al., 2008; Abe and Barber, 2014; Luo et al, 2016). RAB2B-GARIL5 (Golgi-associated RAB2B interactor-like 5) complex is a regulator of STING in Golgi apparatus and promotes IFN response through regulating phosphorylation of IRF3 by TBK1. The autophagy-related protein such as autophagy-related protein (Atg), ULK1 (a homologue of Atg1), microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain (LC)3 (homologue of yeast Atg8) and Atg9 negatively regulate STING signaling through interfering with STING-TBK1-IRF3 signaling (Saitoh et al., 2009, Tooze et al., 2010; Konno et al., 2013). Atg-mediated degradation modulates baseline of STING protein level, but it does not impact the trafficking of STING. The function of STING is regulated by post-translational mechanism such as TRIM32 and TRIM56, that conjugate K63-linked polyubiquitination on STING and promote the recruitment of TBK1 (Tsuchida et al., 2010). ER-associated E3 ligase, AMFR, catalyzes the K27-linked polyubiquitination of STING together with INSIG1 (Wang et al., 2014). K27-linked polyubiquitination on STING induces TBK1 recruitment and activation. iRhom2, which recruits de-ubiquitination enzyme EIF3S, maintains the stability STING through removal of its K48-linked polyubiquitin chains. STING translocates from ER to Golgi apparatus and then moves to late endosome/lysosome (Dobbs et al., 2015). Helix aa281-297 of STING is shown to be degraded through V-ATPase in endosome/lysosome. The blockade of V-ATPase suppresses STING degradation, which potentially leads to enhance STING signaling (Gonugunta et al., 2017).

onse through regulating phosphorylation of IRF3 by TBK1. The autophagy-related protein such as autophagy-related protein (Atg), ULK1 (a homologue of Atg1), microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain (LC)3 (homologue of yeast Atg8) and Atg9 negatively regulate STING signaling through interfering with STING-TBK1-IRF3 signaling (Saitoh et al., 2009, Tooze et al., 2010; Konno et al., 2013). Atg-mediated degradation modulates baseline of STING protein level, but it does not impact the trafficking of STING. The function of STING is regulated by post-translational mechanism such as TRIM32 and TRIM56, that conjugate K63-linked polyubiquitination on STING and promote the recruitment of TBK1 (Tsuchida et al., 2010). ER-associated E3 ligase, AMFR, catalyzes the K27-linked polyubiquitination of STING together with INSIG1 (Wang et al., 2014). K27-linked polyubiquitination on STING induces TBK1 recruitment and activation. iRhom2, which recruits de-ubiquitination enzyme EIF3S, maintains the stability STING through removal of its K48-linked polyubiquitin chains. STING translocates from ER to Golgi apparatus and then moves to late endosome/lysosome (Dobbs et al., 2015). Helix aa281-297 of STING is shown to be degraded through V-ATPase in endosome/lysosome. The blockade of V-ATPase suppresses STING degradation, which potentially leads to enhance STING signaling (Gonugunta et al., 2017).

references :

Cai, X., Chiu, Y. H., & Chen, Z. J. (2014). The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Molecular cell, 54(2), 289-296.

Chen, Q., Sun, L., & Chen, Z. J. (2016). Regulation and function of the cGAS–STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nature immunology, 17(10), 1142.

Liu, X., & Wang, C. (2016). The emerging roles of the STING adaptor protein in immunity and diseases. Immunology, 147(3), 285-291.

Hu, M.M., Yang, Q., Xie, X.Q., Liao, C.Y., Lin, H., Liu, T.T., Yin, L. and Shu, H.B. (2016). Sumoylation promotes the stability of the DNA sensor cGAS and the adaptor STING to regulate the kinetics of response to DNA virus. Immunity, 45(3), pp.555-569.

Xiong, M., Wang, S., Wang, Y. Y., & Ran, Y. (2018). The Regulation of cGAS. Virologica Sinica, 1-8.

Sun, L., Wu, J., Du, F., Chen, X., & Chen, Z. J. (2013). Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science, 339(6121), 786-791.

Seo, Gil Ju, et al. “TRIM56-mediated monoubiquitination of cGAS for cytosolic DNA sensing.” Nature communications 9.1 (2018): 613.

Ishikawa, H., & Barber, G. N. (2008). STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature, 455(7213), 674.

Abe, T., & Barber, G. N. (2014). Cytosolic DNA-Mediated, STING-Dependent Pro-Inflammatory Gene Induction Necessitates canonical NF-κΒactivation Through TBK1. Journal of virology, JVI-00037

Luo, W. W., Li, S., Li, C., Lian, H., Yang, Q., Zhong, B., & Shu, H. B. (2016). iRhom2 is essential for innate immunity to DNA viruses by mediating trafficking and stability of the adaptor STING. Nature immunology, 17(9), 1057.

Saitoh, T., Fujita, N., Hayashi, T., Takahara, K., Satoh, T., Lee, H., Matsunaga, K., Kageyama, S., Omori, H., Noda, T. and Yamamoto, N., (2009). Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(49), pp.20842-20846.

Tooze, S.A., Jefferies, H.B., Kalie, E., Longatti, A., Mcalpine, F.E., Mcknight, N.C., Orsi, A., Polson, H.E., Razi, M., Robinson, D.J. and Webber, J.L., (2010). Trafficking and signaling in mammalian autophagy. IUBMB life, 62(7), pp.503-508.

Konno, H., Konno, K., & Barber, G. N. (2013). Cyclic dinucleotides trigger ULK1 (ATG1) phosphorylation of STING to prevent sustained innate immune signaling. Cell, 155(3), 688-698.

Tsuchida, T., Zou, J., Saitoh, T., Kumar, H., Abe, T., Matsuura, Y., Kawai, T. and Akira, S., (2010). The ubiquitin ligase TRIM56 regulates innate immune responses to intracellular double-stranded DNA. Immunity, 33(5), pp.765-776.

Wang, Q., Liu, X., Cui, Y., Tang, Y., Chen, W., Li, S., Yu, H., Pan, Y. and Wang, C., (2014). The E3 ubiquitin ligase AMFR and INSIG1 bridge the activation of TBK1 kinase by modifying the adaptor STING. Immunity, 41(6), pp.919-933.

Dobbs, N., Burnaevskiy, N., Chen, D., Gonugunta, V. K., Alto, N. M., & Yan, N. (2015). STING activation by translocation from the ER is associated with infection and autoinflammatory disease. Cell host & microbe, 18(2), 157-168.

Gonugunta, V. K., Sakai, T., Pokatayev, V., Yang, K., Wu, J., Dobbs, N., & Yan, N. (2017). Trafficking-Mediated STING Degradation Requires Sorting to Acidified Endolysosomes and Can Be Targeted to Enhance Anti-tumor Response. Cell reports, 21(11), 3234-3242.

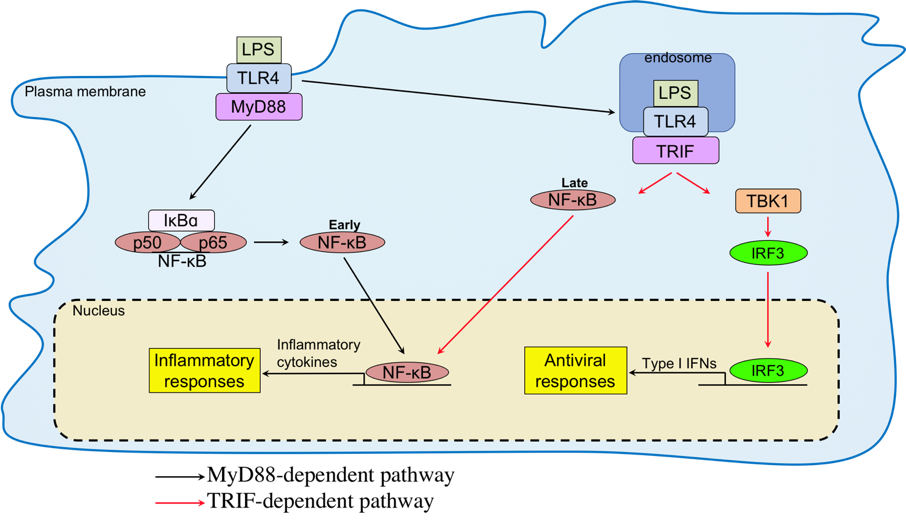

TLRs are comprised of about 10 members in mammals and consist of extracellular leucine-rich repeats and cytoplasmic Toll/interleukin-1-receptor (TIR) domain. TLR4 recognizes bacterial lipopolysaccharide (Alexander and Rietschel, 2001; Bell, 2008). TLR2 and TLR5 recognize other bacterial components such as peptidoglycan and flagellin, respectively. Unlike these TLRs expressed on the cell surface, TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9 are exclusively expressed in the endosomes and recognize viral or bacterial nucleic acids such as double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) or CpG DNA, respectively (Broz and Monack, 2013; Pandey et al., 2014). All these TLRs initiate signaling pathways upon PAMPs recognition by recruiting a TIR domain-containing adapter proteins such as MyD88, TIRAP, TRIF and/or TRAM, and activate the transcription factors such as NF-kB or IRF family members such as IRF3 and IRF7 to induce the transcription of target genes including inflammatory cytokines (IL6, TNF, etc) and type I IFNs (Kagan et al., 2008; Kawai and Akira, 2010).

RLRs are a family of DExD/H box RNA helicases that recognize viral RNA in the cytoplasm. RLRs consist of RIG-I and MDA5, which share structure similarities such as an N terminal region consisting of tandem caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD), a central DExD/H box RNA helicase domain responsible for viral RNA recognition and C-terminal domain (CTD) that is involved in autoregulation in the case of RIG-I (Loo and Gale, 2011). In an active state, the CARD domain of RIG-I binds to its central helicase domain. After binding to viral RNA, cytosolic RIG-I and MDA5 undergo conformational changes and associate with the CARD domain of IPS-1, an adapter molecule localized at the mitochondrial outer membrane. IPS-1 subsequently activates IRF3 and NF-κB by recruiting their upstream protein kinases such as TBK1 and IKKa/b, respectively(Kawai et al., 2005; Seth et al., 2005).

RIG-I recognizes 5′-triphosphate RNA (5′-ppRNA) as well as short dsRNA derived from Sendai virus and Newcastle disease virus of Paramyxoviridae virus family, influenza A virus of the Orthomyxoviridae virus family, Japanese encephalitis virus of Flaviviridae family, vesicular stomatitis virus of the Rhabdovirus family whereas MDA5 recognizes long dsRNA derived from poliovirus of the Picornaviridae family and encephalomyocarditis virus (Pandey, 2014). RLRs are expressed in various cells including immune and non-immune cells, which are in contrast to nucleic acids-recognizing TLRs that are abundantly expressed on innate immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. Thus, RLRs are cytoplasmic sensors for RNA viruses that are infected into cells whereas TLRs recognize viruses that are engulfed and lysed in the endosomes by innate immune cells.

Host cells also express a cytosolic sensor responsible for DNA recognition. cGAS are identified as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor. cGAS is an enzyme that synthesizes cGAMP from ATP and GTP following binding to viral and host DNA. cGAMP contains two phosphodiester bonds, one between 2′-OH of GMP and 5′-phosphate of AMP and the others between 3′-OH of AMP and 5′-phosphatase of GMP (Zhang et al., 2013) and acts as the second messenger that binds to the adaptor protein STING on endoplasmic reticulum (ER). STING traffics from the ER to perinuclear region including the Golgi apparatus, then forms punctate structures along with TBK1. TBK1 phosphorylates IRF3 and phosphorylated IRF3 forms a dimer and translocate into nucleus to express type I IFN genes. Therefore, translocationof STING to Golgi is a hallmark of activation of STING. Various types of DNA viruses such as human papillomavirus, herpes simplex virus, adenovirus, hepatitis B virus infect to the host cells and release their own DNA genome to cytoplasm of host cells. cGAS in host cells binds to the released viral DNA and cGAS recognition initiates innate immune responses. cGAS also recognizes retroviruses such as HIV-1, which produces intermediate DNA from viral RNA genome during expansion (Ma and Damania, 2016). Also, cGAS binds to host cell DNA when cells are damaged by environmental stresses, aging, and drug, and this response contributes to autoimmunity and inflammation as well as potentiation of acquired immune responses to cancers (Lau et al., 2015; Mackenzie et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017, Xiong et al 2018).

-from my Ph.D thesis

references :

Alexander, C., & Rietschel, E. T. (2001). Invited review: bacterial lipopolysaccharides and innate immunity. Journal of endotoxin research, 7(3), 167-202.

Bell, E. (2008). Innate immunity: TLR4 signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology, 8(4), 241.

Broz, P., & Monack, D. M. (2013). Newly described pattern recognition receptors team up against intracellular pathogens. Nature Reviews Immunology, 13(8), 551.

Pandey, S., Kawai, T., & Akira, S. (2014). Microbial sensing by Toll-like receptors and intracellular nucleic acid sensors. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, a016246.

Kagan, J. C., Su, T., Horng, T., Chow, A., Akira, S., & Medzhitov, R. (2008). TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-β. Nature immunology, 9(4), 361.

Kawai, T., and Akira, S. (2010). The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384.

Loo, Y. M., & Gale Jr, M. (2011). Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity, 34(5), 680-692.

Kawai, T., Takahashi, K., Sato, S., Coban, C., Kumar, H., Kato, H., Ishii, K.J., Takeuchi, O., and Akira, S. (2005). IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat. Immunol. 6, 981–988.

Seth, R.B., Sun, L., Ea, C. K., and Chen, Z.J. (2005). Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 122, 669–682.

Ma, Z., & Damania, B. (2016). The cGAS-STING defense pathway and its counteraction by viruses. Cell host & microbe, 19(2), 150-158.

Lau, L., Gray, E. E., Brunette, R. L., & Stetson, D. B. (2015). DNA tumor virus oncogenes antagonize the cGAS-STING DNA-sensing pathway. Science, 350(6260), 568-571.

Mackenzie, K.J., Carroll, P., Martin, C.A., Murina, O., Fluteau, A., Simpson, D.J., Olova, N., Sutcliffe, H., Rainger, J.K., Leitch, A. and Osborn, R.T., 2017. cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature, 548(7668), p.461.

Wang, H., Hu, S., Chen, X., Shi, H., Chen, C., Sun, L., & Chen, Z. J. (2017). cGAS is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201621363.

Yang, H., Wang, H., Ren, J., Chen, Q., & Chen, Z. J. (2017). cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(23), E4612-E4620.

Xiong, M., Wang, S., Wang, Y. Y., & Ran, Y. (2018). The Regulation of cGAS. Virologica Sinica, 1-8

Host immune response is a defense system to eliminate to invading pathogens including bacteria, fungi, and virus, and largely classified into innate and acquired immune responses. Innate immune response is the first line of host defense system that is triggered upon sensing molecules specific in pathogens, which are called Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) with Pattern-Recognition Receptor (PRRs) that are expressed in various types of host cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells, endothelial cells, epithelial cells and lymphocytes (Kawai et al., 2010; Iwasaki et al., 2015). Among them, dendritic cells and macrophages are the major innate immune cells that produce large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons (IFNs) and function as antigen presenting cells that potentiate acquired immunity. Releasing cytokines and type I IFNs lead to production of anti-bacterial or anti-viral proteins to prevent pathogen infections. In addition, cytokine production and antigen presentation by innate immune cells induce acquired immune activation, which includes antibody production by plasma cells and T cell-specific killer activity.

So far, numerous PRRs have been identified. These include Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-Like Receptor (RLRs), and intracellular sensor for DNA such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS). They recognize different or overlapped PAMPs at different organelles such as the transmembrane, endosomes, nucleus or cytoplasm, and activate distinct signaling pathways. These differences result in appropriate immune responses specific to given pathogens (Kawai et al., 2011).

-part of my thesis Ph.D degree

References :

Kawai, T., and Akira, S. (2010). The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384.

Kawai, T., & Akira, S. (2011). Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity, 34(5), 637-650.

Thanks for joining me!

Good company in a journey makes the way seem shorter. — Izaak Walton